TRANSGOV PI prof. Aarti Gupta was interviewed by Wageningen University on TRANSGOV’s research visit to Ethiopia and COP29. Read the news article here.

TRANSGOV PI prof. Aarti Gupta was interviewed by Wageningen University on TRANSGOV’s research visit to Ethiopia and COP29. Read the news article here.

At COP29 in Baku, TRANSGOV PI Aarti Gupta spoke in a press conference about transparency and accountability in the UNFCCC. In this press conference, Aarti Gupta provided reflections on COP-29 from a Global South perspective.

Key messages:

The Business Standard reported on this press conference:

“Dr. Aarti Gupta from Wageningen University emphasised that transparency was a recurring theme, and stressed the accountability deficit in climate pledges. Accountability mechanisms are limited in the UNFCCC framework, she pointed out. Gupta expressed concern over the reliance on self-reported climate finance data, which often lacks verification and a clear picture of actual flows. Without a standardised, multilateral definition of climate finance, self-reporting by developed countries has often been inadequate in capturing the true extent of contributions, she said. Dr. Gupta also raised a red flag on the potential risks of speculative geoengineering solutions, such as solar radiation modification, being discussed as a last-resort climate strategy. These risky, untested methods could detract from meaningful action, she argued. There is serious pushback from the Global South against these options, Gupta stated, underscoring the urgency for strengthened accountability to avoid resorting to these high-stakes technologies.”

Key Highlights:

2024 is an important year for transparency in the international climate regime. By the end of the year, the first biennial transparency reports (BTRs) are due under the Paris Agreement’s new enhanced transparency framework. At COP29 there will be much buzz around these new transparency reports. But there are also other important transparency matters on the agenda which may attract less limelight but are equally crucial. This blogpost discusses four crucial issues related to the politics of transparency at COP29 that will have implications for how transparency continues to evolve under the international climate regime.

Under the enhanced transparency framework of the Paris Agreement, countries are to submit their first biennial transparency reports (BTRs) by the end of this year.[1] At the time of writing, four countries have submitted their first biennial transparency report: Andorra, Guyana, Japan and Panama.[2] COP29 will set the tone for how the submission or non-submission of biennial transparency reports before the deadline will be dealt with in the international climate regime.

Early submitters of biennial transparency reports can expect to be celebrated. Indeed, the President-Designate of COP29 wrote a letter to Parties, highlighting the importance of transparency and encouraging countries to submit their first biennial transparency reports in advance of COP29. Those who have done so will get special limelight. For example, there will be a side-event organized by the UNFCCC Secretariat dedicated to Guyana’s transparency report and its experience with the technical review process of this report.[3] The Executive Secretary of the UNFCCC also had special praise for Andorra and Guyana for being the first to submit a biennial transparency report, and he encouraged all countries to submit a report by the end of this year.

To add further momentum, the COP29 presidency has also hosted, earlier this year, a High-Level Dialogue on Climate Transparency in Baku, and a High-level Dialogue on Global Climate Transparency during the 79th session of the UN General Assembly. These efforts are to culminate in the establishment of the Baku Global Climate Transparency Platform and the adoption of a Transparency Declaration at COP29, both of which are to provide a further push to ensuring as many countries as possible submit their first biennial transparency report as soon as possible.

Yet where there is fame for the early submitters, there is also potential blame for those who do not manage to submit their first biennial transparency report before the end of the year. To some this might seem justified. After all, it is a multilaterally agreed rule to submit these reports. But the question is: are we celebrating or blaming countries based on the right metric? If a country is good at reporting, that is great, but it does not necessarily mean the country is also a climate champion. On the other hand, countries that are late in submitting reports might still be among those with very low emissions.[4] In other words, it should be the content of the report (relating to the climate actions undertaken in the country) that should be determining who is celebrated and who is not, rather than simply ticking the box of submitting the report.

A further problematic element of using submissions of biennial transparency reports to celebrate or blame countries, is that it is likely that all or most developed countries will manage to submit their reports by the deadline while many developing countries will struggle to do so. This is to be expected because the enhanced transparency framework basically requires developing countries to ‘catch up’ to the level of reporting previously applicable to developed countries under pre-Paris rules, especially on the greenhouse gas inventory and mitigation front.[5] In other words, it is a tilted playing field in terms of countries’ readiness to be submitting these new reports. And while there are various support initiatives to help developing countries prepare for their biennial report submissions, these also have their shortcomings, as will be discussed below.

For a number of years, countries have negotiated over whether and how support for reporting under the Paris Agreement needs to be reconfigured. Developing countries argue that support is insufficient to cover all costs. Moreover, developing countries argue that the modalities for support provided by the Global Environmental Facility are not fit-for-purpose. This because of constraints preventing national ministries in developing countries to use Global Environmental Facility funding to establish permanent positions to manage international reporting. Developing countries, with South Africa being particularly vocal on this, argue that the funding infrastructure perpetuates a reliance on external consultants and does not allow for the building of capacity within the government. To address this issue, the Global Environmental Facility would need to reconfigure its rules attached to funding provision. However, developed countries have argued that the UNFCCC is not the space to be doing this, arguing that the board of the World Bank is responsible for negotiating these matters. This stalemate has continued for multiple UNFCCC negotiation sessions.

One important development in the support for reporting landscape is that COP29 will see the launch of the Baku Transparency Platform. It was developing countries who asked last year for a Dubai Transparency Platform to ramp up support for developing countries to implement the enhanced transparency framework. Some countries will be happy with the establishment of the Baku Transparency Platform. For others, this is more of the same: just another venue for training and workshops, without any fundamental rethinking of support mechanisms or how they can be made more programmatic and geared toward building domestic capacities. But if domestic capacities are to be developed for reporting, a further important question is: capacities to report on what? This brings us to another topic to watch at COP29: whether the ever-dominant focus on mitigation-related reporting is slowly making place for reporting on adaptation and loss and damage.

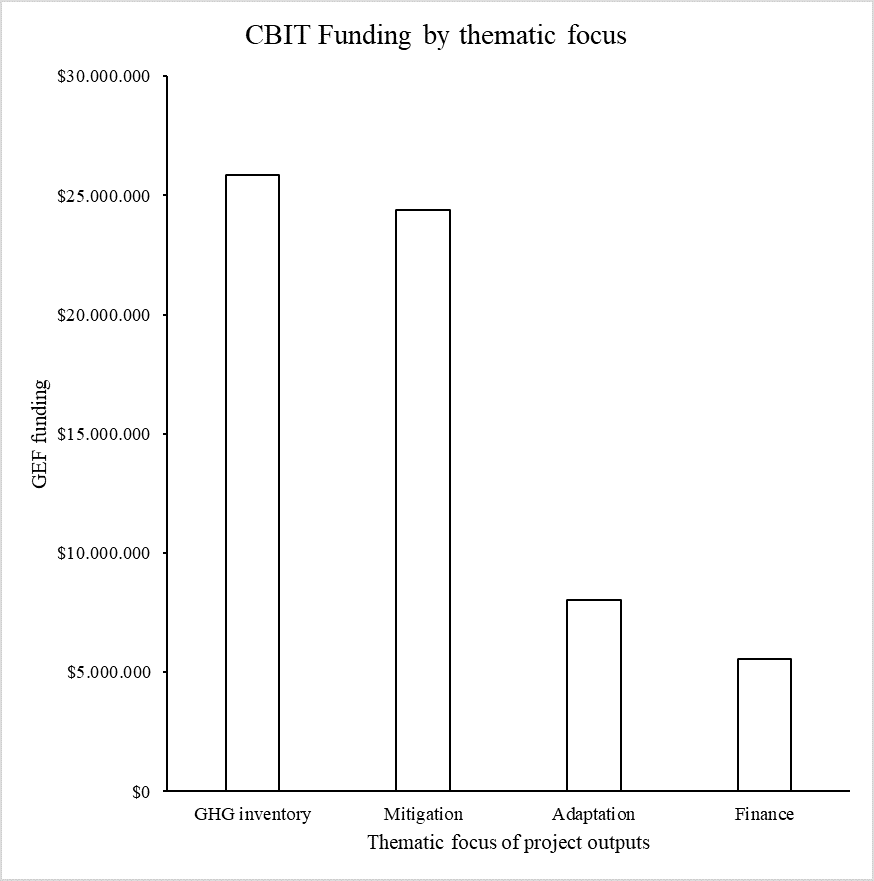

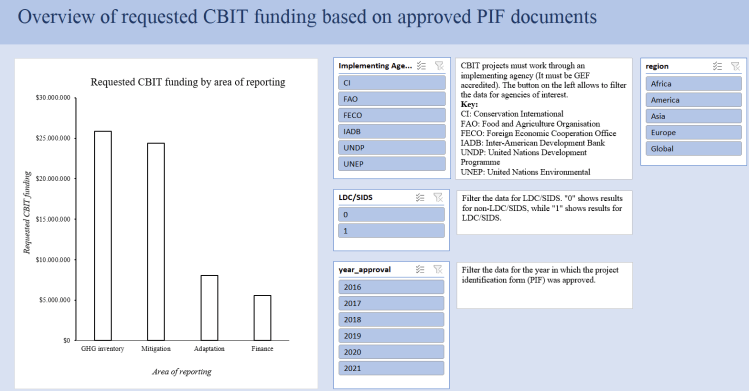

Reporting on adaptation and loss and damage has often been in the shadow of reporting on greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation actions. Under the enhanced transparency framework reporting on greenhouse gas inventories and mitigation actions is mandatory whereas reporting on adaptation and loss and damage is voluntary. There is extensive, multilaterally agreed guidance for reporting on greenhouse gas inventories, while reporting guidance for adaptation and loss and damage remains limited. There is also evidence that internationally supported capacity building projects for reporting often focus on mitigation reporting rather than adaptation and loss and damage.[6]

But over the last years, adaptation and loss and damage reporting are catching up, be it from a far distance. At COP27 it was decided that countries could on a voluntary basis submit their adaptation chapters in their biennial transparency reports for technical review, and that they could highlight specific sections (importantly, one of them could be loss and damage) for specific attention. COP28 further included an outcome that requested the Executive Committee of the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage to produce further guidance on loss and damage reporting,[7] and it requested the secretariat to draft a synthesis report of loss and damage information in biennial transparency reports. In addition, various non-state actors have stepped in with working papers on how countries might want to go about loss and damage reporting under the enhanced transparency framework.[8]

COP29 might further this trend of lifting the importance of adaptation and loss and damage reporting. A case in point here is the ongoing process of developing indicators to track progress on the global goal on adaptation, set to conclude next year at COP30. However, it is not self-evident that countries will in practice report on adaptation and loss and damage in their first biennial transparency reports, even for developing countries for whom these are important topics. After all, adaptation and loss and damage remain voluntary elements of reporting, and some have argued that countries should first and foremost focus on the mandatory elements of the enhanced transparency framework.[9] It thus remains to be seen if and how adaptation and loss and damage will be reported on in the first round of biennial transparency reports. This will be determined, not in the least, by developing countries’ expectations on what reporting on adaptation and loss and damage might deliver for them. Indeed, whether transparency translates into action is not self-evident, a point to which we turn next.

In October 2023, the UNFCCC secretariat published a synthesis report of the fifth biennial reports submitted by developed countries under pre-Paris reporting rules. While biennial reports might sound technical and dull, the careful reader of the synthesis report will find pearls of politically salient pieces of information.

First, the synthesis report noted, in paragraph 182, that self-reported projected emissions by developed countries showed that ‘no Party will achieve its targeted level of emissions in 2030 set out in its NDC.’ This is a consequential finding. It means that developed countries must formulate and implement additional climate policies before the end of this decade to meet their targets. While there is still time for developed countries to do so, this finding does merit special attention in the future from the international community in terms of following up on whether developed countries have taken the necessary measures to inch closer towards meeting their 2030 NDC targets. The issue of self-reported projections was also the focus of a collaborative TRANSGOV-CEEW report, which found that while globally emissions need to reduce by at least 43% by 2030, developed countries’ NDCs only add up to 36%, and that self-reported projections point to a mere 11% reduction. In other words, these self-reported projections are a potentially powerful tool to track progress in meeting NDCs (as TRANSGOV reported on also earlier at COP28 as contained in the post below).

TRANSGOV PhD @Max_vDeursen reporting from #COP28! 🎥 Unveiling the significance of a little-known climate transparency report 📊 (See https://t.co/suk9W9Gg2U para. 182 and 150). pic.twitter.com/P4aj7VtvfD

— TRANSGOV (@transgov_wur) December 3, 2023

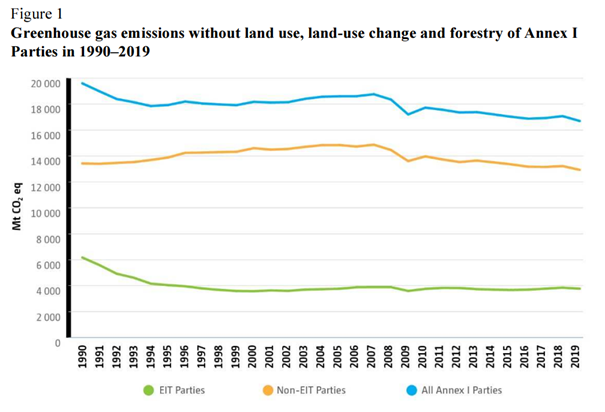

Secondly, the synthesis report also notes, in paragraph 32, that emissions in developed countries only decreased by 17.3 per cent between 1990 and 2021.[10] This is politically salient in the context of the Global Stocktake outcome, which noted ‘with concern the pre-2020 gaps in both mitigation ambition and implementation by developed country Parties and that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change had earlier indicated that developed countries must reduce emissions by 25–40 per cent below 1990 levels by 2020, which was not achieved.’[11] The synthesis report of self-reported emission information by developed countries thus contains a final verdict on whether certain benchmarks of collective action were reached.

Finally, the synthesis report also covers reporting on the controversial topic of climate finance. Here it found, based on self-reported data by developed countries, that ‘climate finance, including climate-specific and core/general contributions, provided by developed countries to developing countries averaged USD 51.6 billion annually in 2019–2020’.[12] This is again politically salient information in the context of the goal for developed countries to provide 100 billion in climate finance annually by 2020.

At COP28, countries did not manage to reach consensus on the consideration of this synthesis report. Then at the opening of the June sessions at the 60th session of the subsidiary bodies, Brazil made a small fuzz in the opening plenary demanding this item be discussed in a dedicated negation room. The crux in these Bonn negotiation sessions was what to do with the pieces of information outlined above. Negotiations led to an informal note, which contained an option to simply note the synthesis report and an option to signal out key pieces of vital information and invite developed countries to submit additional information on how they have used the outcomes of this consideration to take on additional policy measures. But no agreement was reached in Bonn on this matter,[13] meaning all options are still on the table at COP29, with implications for how transparency gets translated into action.

Transparency will feature prominently at COP29, including in the focus of the presidency’s events and diplomatic efforts. There will be celebration of those countries who already submitted their first biennial transparency reports under the enhanced transparency framework and there will be a strong call for those who have not yet done so to submit before the deadline of December 31 this year. While the start of the enhanced transparency framework and early biennial transparency report submissions will catch the limelight, crucial discussions on climate transparency will take place in smaller negotiation rooms or side events. As outlined in this blogpost these relate to how to translate key findings coming out of the pre-Paris transparency reports into action, how to rethink support for reporting and new developments in reporting on adaptation and loss and damage.

TRANSGOV will follow these matters at COP29 and continue to critically interrogate what transparency delivers in practice and whose priorities are reflected in the further implementation of the enhanced transparency framework.

[1] Least developed countries and small island developing states can submit at their discretion.

[2] As of November 6, 2024. Available at https://unfccc.int/first-biennial-transparency-reports.

[3] This side-event is titled ‘Learning from BTR reviews: Experiences from the in-country review of Guyana’s first BTR’ and will take place on Monday 18th November at 15:00 in side-event room 7. Available at: https://seors.unfccc.int/applications/seors/reports/events_list.html?session_id=COP%2029.

[4] See also: Weikmans, R., & Gupta, A. (2021). Assessing state compliance with multilateral climate transparency requirements: ‘Transparency Adherence Indices’ and their research and policy implications. Climate Policy, 21(5), 635–651. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2021.1895705. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14693062.2021.1895705#abstract.

[5] Mayer, Benoit, Transparency under the Paris Rulebook: An Enhanced Transparency Framework? (September 3, 2019). (2019) 9:1 Climate Law 40-64, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3447126

[6] Konrad, S., van Deursen, M., & Gupta, A. (2021). Capacity building for climate transparency: neutral ‘means of implementation’ or generating political effects? Climate Policy, 22(5), 557–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2021.1986364

[7] See the draft outline of this loss and damage reporting guidance here: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/BTR%20Guidelines%20Outline.pdf

[8] See, for example: https://www.ceew.in/sites/default/files/ceew-what-gets-measured-gets-done-transparency-for-loss-and-damage-04nov24-web.pdf; https://climateanalytics.org/publications/using-existing-databases-to-report-on-loss-and-damage-in-biennial-transparency-reports-under-the-unfccc .

[9] Pulles, T., & Hanle, L. (2023). A fit for purpose approach for reporting and review under UNFCCC’s Enhanced Transparency Framework. Carbon Management, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/17583004.2023.2235568.

[10] Excluding emissions from Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry.

[11] 1/CMA.5, para. 17. https://undocs.org/FCCC/PA/CMA/2023/16/Add.1

[12] 1/CMA.5, para. 202. https://undocs.org/FCCC/PA/CMA/2023/16/Add.1

[13] For an article further discussion this see: https://www.twn.my/title2/climate/info.service/2024/cc240606.htm

National stakeholder dialogue with climate transparency researchers

Thursday 24 October 2024, 09:30 – 16:00 hours (EAT)

Location: Kuriftu Resort & Spa Bishoftu, kebeke 15, Bishoftu, Ethiopia

This dialogue aims to bring together academics and diverse stakeholders in Ethiopia, with the core objective being to reflect on whether and how Ethiopia’s engagement with UNFCCC transparency arrangements could help advance its priorities to bring about domestic benefits.

Ethiopia has been actively involved in international climate change efforts since the 1990s, ratifying the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1994 and the Paris Agreement in 2017. The primary goal of this international agreement is to limit the rise of human-caused global temperature while requiring signatories to be transparent about their climate actions, especially those related to climate mitigation. Although not mandatory for Least Developed Countries (LDCs), Ethiopia has engaged in the UNFCCC transparency requirements by submitting three National Communications (NCs) and one Biennial Update Report (BUR). With technical support from international capacity-building providers, these reports mainly focus on a detailed assessment of national greenhouse gas inventories and the country’s commitments to mitigation actions. But with less focus on adaptation, loss and damage assessments, and climate finance tracking.

Both internationally and nationally, engaging with the UNFCCC through transparency reporting is assumed to provide domestic benefits, such as utilizing these reports in policy formulation, attracting international climate finance, and participating in future carbon markets. In practice, however, it is unclear whether this engagement is delivering those domestic benefits for Ethiopia. Another unexplored yet highly contested topic is whether LDCs such as Ethiopia, which have an insignificant contribution to global greenhouse emissions, should prioritize mitigation actions (as required by the UNFCCC) over their other urgent development challenges.

The international research project ‘Assessing the Transformative Potential of Climate Transparency’ (TRANSGOV), based at Wageningen University in the Netherlands, addresses these knowledge gaps. TRANSGOV’s research has produced several key insights that challenge the status quo of what is often believed to be the enabling role of ever-greater levels of transparency in climate governance. These findings suggest that the current status quo of (largely mitigation-focused) climate reporting may not be conducive (and potentially even be a hurdle) to realizing specific domestic climate action priorities in LDCs.

In 2024, a new Enhanced Transparency Framework (ETF) under the Paris Agreement has become operational, under which even more stringent mitigation-related transparency is now required from countries. Adherence to this new framework through submitting Biennial Transparency Reports (BTR) is mandatory for most countries but still voluntary for LDCs. Ethiopia has already expressed interest in submitting a BTR to the UNFCCC. Consecutively, international capacity-building support initiatives are underway to help the country comply with this specific transparency requirement. This is a thus crucial moment to assess whether and how the country’s previous engagement with the UNFCCC has yielded domestic benefits. It is timely to ask: What does Ethiopia’s engagement in UNFCCC transparency arrangements deliver? Where should Ethiopia’s reporting priorities focus, and what technical capacity-building support is needed to realize such priorities? TRANSGOV facilitates these questions during this national stakeholder dialogue.

Prof. Aarti Gupta

Wageningen University & Research

Aarti Gupta is Principal Investigator of the TRANSGOV project. She is a Professor of Global Environmental Governance with the Environmental Policy Group, Department of Social Sciences, Wageningen University. Her research is in the field of global environmental and climate governance, with a focus on transparency and accountability and the challenges of anticipatory governance of novel technologies, including climate engineering. She has published extensively in these fields, including the edited volume, Transparency in Global Environmental Governance: Critical Perspectives (2014, MIT Press). She holds a PhD from Yale University and is a member of the Scientific Steering Committee of the International Earth System Governance Research Alliance.

Mr. Benti Firdissa

Rahwa Kidane

Wageningen University & Research

Rahwa Kidane is a postdoctoral researcher in the Environmental Policy Group at Wageningen University and Research. She holds a PhD in Environmental Studies from the University of Adelaide, with a focus on climate change impacts, vulnerability and adaptation in developing countries. Within TRANSGOV projects, she will facilitate analysis of Ethiopia’s participation in UNFCCC climate transparency arrangements and its implications for national adaptation actions. Her work will also investigate whether radical transparency – or the generation of ever more climate-related information enabled through satellite and other remote sensing technologies – hold responsible actors accountable, enhances trust and consecutively accelerates climate action in India and Ethiopia.

Max van Deursen

Wageningen University & Research

Max van Deursen has a background in environmental science and global governance. He has a master’s degree in Climate Studies from Wageningen University with a specialization in climate policy and sustainable development diplomacy. Through engagement in several UN conferences as the Dutch youth representative to the UN and as an intern at the UNFCCC secretariat Max has first-hand experience with climate negotiations. He is one of two TRANSGOV PhDs, with a focus on assessing how participation in climate transparency arrangements relates to domestic climate action. He will also critically examine the workings of transparency mechanisms under the UNFCCC, including the Enhanced Transparency Framework.

| 9:30 | Registration |

| 10:00 | Welcome and opening Prof. Aarti Gupta, Wageningen University & Research Mr. Benti Firdissa |

| 10:30 | Presentations 1. What are the UNFCCC transparency arrangements? Mr. Max van Deursen, Wageningen University & Research 2. Ethiopia’s engagement in UNFCCC transparency arrangements Dr. Rahwa Kidane, Wageningen University & Research |

| 11:00 | Interactive session 1: What has engagement in transparency arrangements delivered? In this interactive session, we will discuss Ethiopia’s past engagement with UNFCCC transparency arrangements. Ethiopia has submitted three National Communications (NCs) and one Biennial Update Report (BUR). We will discuss what the utility and impact of generating such reports has been for Ethiopia. |

| 12:30 | Lunch break |

| 14:00 | Interactive session 2: How to shape future engagement in transparency arrangements? In this interactive session, we will look ahead to Ethiopia’s future engagement with UNFCCC transparency arrangements. We will explore the question: where should Ethiopia’s future reporting priorities to the UNFCCC focus on, and how can international capacity-building efforts support these priorities? |

| 15:30 | Closing and reflection |

| 16:00 | Drinks, snacks and networking |

Rahwa Kidane (rahwa.kidane@wur.nl)

Max van Deursen (max.vandeursen@wur.nl)

This TRANSGOV event is financed by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) Impact Explorer.

An Academic-Practitioner Dialogue on the sidelines of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) June negotiating session in Bonn, 2024

The TRANSGOV team was in Bonn in June 2024 to organize an academic-practitioner dialogue bringing together climate transparency negotiators from Least Developed Countries (LDCs) to advance the aims of our recently awarded NWO-impact explorer project.

In 2023-24, a significant share of the core budget of the UNFCCC secretariat went towards transparency-related activities, including activities intended to encourage and support all developing countries to adhere to global reporting requirements regarding their climate actions and aspirations. An essential question for the TRANSGOV project is whether ever growing demands for more climate transparency from all countries are generating domestic benefits.

TRANSGOV insights from South Africa and India suggest that benefits are often hard to realize. More importantly, what transparency is delivering in practice domestically for countries is hardly assessed, and very little is known about the domestic consequences for LDCs in particular of engaging in global transparency arrangements.

To bring ongoing research insights to and learn from the LDC context, the TRANSGOV project organized an academic-practitioner dialogue entitled: Questioning the Status Quo: What does LDC engagement in UNFCCC transparency arrangements deliver? This one-of-a-kind dialogue was meant to delve into the complexity of climate transparency and its consequences for LDCs, and was the first activity of our Impact Explorer grant, intended to generate impact from existing research findings in new contexts.

The event took place on 8 June 2024, from 9:30 a.m. to 2 p.m., and was hosted at the German Institute for Development and Sustainability (IDOS), Bonn, on the sidelines of the UNFCCC Subsidiary Bodies negotiating session (SB-60).

A Warm Welcome and Setting the Stage

The event began with breakfast, where attendees could mingle and register for the dialogue. Following this, after a short introduction by the TRANSGOV project leader, Prof. Aarti Gupta, Emelie Broek, a TRANSGOV affiliated PhD researcher took over as moderator of the event and two icebreaking activities began. The first icebreaker involved each negotiator sharing a fun fact about their country, with others having to guess where the participant was from. The second icebreaker was targeted towards exploring the perspectives held by the attendees regarding benefits and burdens of engaging in global transparency systems for their countries and the extent of their engagement and experience with UNFCCC transparency-related events thus far. These events sought to build trust and camaraderie among the participants, and set the stage for further in-depth dialogue.

Diving Deep into LDC Reporting Experiences

The first substantive interactive session of the dialogue consisted of an activity called ‘Appreciative Storytelling’ where participants paired up to share a story of benefit or burden from engaging in global climate transparency systems. In a subsequent plenary session, each participant shared their partner’s story and whether it resonated with them. The stories ranged from an individual transparency practitioner’s professional responsibility to their country’s experience and reflections about the scope and practices of UNFCCC transparency mechanisms. The rich plenary discussion yielded competing insights. For example, some participants stated that, despite its limitations, the transparency process had resulted in improved intra-governmental collaboration and data management within their respective countries. However, there was also a general sentiment that there is limited scope to push back against globally set transparency requirements, even where these may not fully resonate with domestic priorities. This provided an avenue to think through, in the second half of the dialogue, what opportunities existed to address this potential disjunct between global and domestic priorities.

A short mid-morning coffee break provided a much-needed pause, allowing participants to network and exchange ideas. After the morning session’s focus on current engagement with transparency requirements, it was now time to look towards the future and to consider whether and how to reimagine transparency mechanisms to tailor them to better serve the unique needs of LDCs.

Reimagining Engagement with Transparency Arrangments

This began with the TRANSGOV team offering an academic perspective on burdens and benefits of global climate transparency, and lessons learned from ongoing global-level analyses and case studies in South Africa and India.

Prof. Aarti Gupta, Dr. Rahwa Kidane, affiliated postdoctoral researcher with TRANSGOV, and Max van Deursen, PhD researcher from TRANSGOV, pitched a shared vision on the scope and practices of transformative transparency to the plenary. They highlighted critical insights from the project’s research thus far, which question the widely held belief that increased transparency inherently benefits all countries. They also presented and discussed a visualised alternative transparency framework that may better serves the needs of LDCs.

This was followed by a second interactive session called ‘Rich Picture’. For this activity, the participants were divided into groups of three to four. They were then tasked with collaboratively developing an alternative vision for engaging in global transparency arrangements, by visually representing their ideas. This creative activity allowed participants to think beyond established paradigms, both in the final product of a reimagined transparency mechanism, but also in the process of creating it.

After 20 minutes, each group was asked to present their picture and engage in discussions with the plenary. It was very interesting to see the ways in which the groups agreed with or differed from the status quo narrative that engagement in global transparency systems provides a range of domestic benefits. Different groups had different approaches to addressing the role for transparency in addressing domestic climate change priorities. One group imagined climate change action as a ‘planetary boat’ that we are all sailing in together, using transparency for building trust and accountability within that framework. Another group emphasised that increased transparency should be linked to providing people with a good and healthy life. Meanwhile, a third group reimagined more bottom-up transparency systems, which would encourage everyday citizens to contribute to climate-related transparency reporting through an app. A recurring theme was that while LDCs have flexibility and discretion in adhering to global reporting requirements, adhering to these requirements was still seen as a de facto obligation—a way to show commitment to the international process and demonstrate national competences but also the need for international support.

Reflection and Closing Address

After the Rich Picture activity, the group reflected on the workshop and its theme in a closing plenary. The participants were provided with three guiding questions to elicit their reflections on the dialogue and UNFCCC transparency mechanisms in general, which generated useful overall insights from different LDC contexts. In closing remarks, Prof. Aarti Gupta thanked the participants and highlighted opportunities in both research and policy practice to reimagine engagement with global UNFCCC transparency obligations for LDCs, now also with the Paris Agreement’s Enhanced Transparency Framework beginning. The dialogue concluded with a networking lunch, where the discussions continued informally.

Looking Forward

This pioneering dialogue was the first of its kind to bring academics and transparency practitioners together, to discuss emerging research findings from TRANSGOV and explore together the real-world impacts of engaging in climate transparency for LDCs. It critically examined the dominant narratives on the benefits of such engagement. It also provided a glimpse into how the goals and mechanisms of transparency can be better imagined to reflect the priorities and realities of LDCs.

By bringing together academics, practitioners, and negotiators from least developed countries in a collaborative setting, the dialogue was able to spark fresh perspectives on the real-world implications of adhering domestically to global transparency obligations. It provided us with first-hand perspectives on how LDCs practically and strategically engage with the global transparency framework to leverage benefits such as financial and technical support. It also provided practitioners with a critical forum to interact with each other and with academics to discuss how to align transparency requirements with their national priorities and capacities. Participants were able to collaboratively explore innovative solutions, share best practices and the challenges of engaging with the current transparency mechanisms. By bridging the gap between academic research and practical implementation, the event sought to ensure societal impact from TRANSGOV research and lay the groundwork for practitioners to be more critical of existing transparency frameworks.

This dialogue established a solid groundwork for continuous and future deliberations regarding climate transparency. Through nurturing a collaborative atmosphere, we hope to have co-generated some avenues for a more meaningful engagement in practice with UNFCCC transparency requirements, for individual LDC transparency practitioners, and for LDCs as a group.

The TRANSGOV team is thankful to all the participants for taking the time to participate in this dialogue, and for their enthusiastic engagement, and to IDOS for providing an ideal venue to host the dialogue. Looking forward, a second dialogue will be held in Ethiopia later this year to delve more deeply into one specific LDC context.

This TRANSGOV event is financed by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) Impact Explorer.

Various transparency related negotiations and events are on the agenda for COP28. In this blogpost I provide a brief overview of four key agenda items. With the transition to the enhanced transparency framework in 2024 around the corner, negotiations at this COP provide an opportunity to shape the new and revisit the old.

Developing countries are not all happy with how support for climate transparency is organized. To address this, the previous CMA (at COP27 in Egypt) was to decide on how to improve the situation. But to no avail. Negotiations continued over the past year and at COP28, countries have another chance to come to agreement.

At the heart of the matter is the question of whether processes under the Global Environmental Facility (GEF), a multilateral fund, should be changed. To prepare for the negotiations in Dubai, countries were invited to make submissions- a good avenue to see what different countries want.

So what do countries want?

The EU, for example, sees various options to deal with capacity challenges. Many of those are for developing countries themselves to take up, such as better defining domestic ‘roles and responsibilities for data collection’ or setting up domestic archiving systems. The EU also sees potential in remote sensingto provide the data for greenhouse gas inventories, especially for countries that do not have the capacity to collect data locally. The US further highlights various existing capacity building initiatives and adds that participation in the transparency arrangements is itself a good way to build capacities and continuously improve.

But some developing countries argue that processes under the Global Environmental Facility need to be changed. First, there is the issue of the amount of funding ($484,000 dollars to prepare one biennial transparency report) is considered insufficient. But that is not the only issue. Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay add that accessing funds is a lengthy process, which is especially problematic for something that has to be done every two years.

South Africa, further adds that the problem also lies in how funds can be spent and that this currently often results in the hiring of consultants rather than establishing posts in the government, which in their view “traps developing countries like South Africa in a perpetual cycle of relying on external service providers instead of building fully functional national systems.”

The LMDC group proposes to establish the ‘Dubai Transparency Platform’ that would run from 2024-2028 to provide additional financial, technical and capacity building support to developing countries, as well as providing a platform for sharing of experiences that could feed into the scheduled revisions of the ETF rules (MPGs) in 2028.

Support for climate transparency was a core part of the enhanced transparency framework’s compromise under the Paris Agreement. But the devil is in the detail. COP28 offers an opportunity to re-negotiate and improve international support for climate transparency.

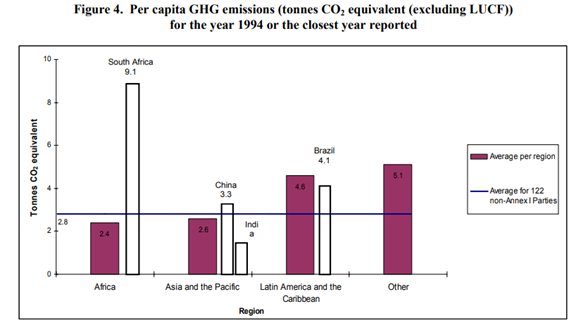

This curious agenda item has been held in abeyance for a long time through various COP agendas. In 2005 the UNFCCC secretariat published a ‘compilation & synthesis report’ of developing countries’ national communications (transparency reports to be submitted every four years). But Brazil contested the way in which the secretariat calculated CO2-equivalent emissions from non-CO2 greenhouse gasses. Brazil argued the methodology used by the secretariat overestimates emissions from short-lived gasses (like methane, which is prevalent in Brazil’s agriculture industry) while underestimating CO2 emissions. Moreover, Brazil considered it inappropriate how Secretariat singled out specific countries in some of the graphs in addendum 2 of the report, for example the figure below.

Source: UNFCCC (2005) ‘Sixth compilation and synthesis of initial national communications from Parties not included in Annex I to the Convention’, p. 10, UN Docs. FCCC/SBI/2005/18/Add.2, available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/docs/2005/sbi/eng/18a02.pdf.

A matter open to interpretation at the time as well was whether such a compilation and synthesis report of non-annex I countries, and consideration thereof by the COP would also apply to future national communications (beyond the initial national communication). Australia on behalf of the Umbrella group was of the view that it should. The report of the SBI24 session (para 32) merely takes note of Australia’s intervention.

Fast forward to the present and the agenda item has been held in abeyance ever since and no subsequent compilation and synthesis reports have been prepared for later rounds of national communications of non-annex I Parties. But in Bonn, earlier this year (2023), consultations took place on this agenda item that had been held in abeyance for so long and the SBI took note (agenda item 4(a)) of the status of submissions of biennial update reports and national communications. Some in the hallways whisper that there is a chance that COP28 will see further movement on this agenda item.

This is all particularly interesting, because in the hallways divergent views are shared on the continuing utility of national communications under the Convention when there is biennial reporting under the Paris Agreement. Developing countries want to keep the national communication process. One of the reasons is that the National Communications are under the Convention and guided by its principles. Moreover, the national communications provide ample space to report in detail on adaptation and vulnerability. Finally, and linking to the previous section, support for national communications is a substantially larger sum of money than for the new biennial transparency reports (even though countries can also apply for a joint grant to write both at once). Whether the revival of this agenda item will change the dynamics over the continued relevance of national communications remains to be seen.

Zooming out a little bit, we are also interested in a larger question: how is transparency implicated in efforts to drive enhanced ambition?

As discussed in previous blogs about COP27 (see here and here) transparency is often actually detached from the places where enhanced ambition is explicitly discussed. How will this pan out at COP28? There are a number of agenda items explicitly or implicitly dealing with the question of enhanced ambition. Here we discuss how transparency is or could be implicated.

First, CMA5 will see a ‘high-level ministerial round table on pre-2030 ambition.’The proceedings of last year’s round table do not include a single mention of the transparency framework or transparency reports submitted under it. A particularly pertinent document that should feed into this round table is the secretariat’s compilation and synthesis report of developed countries’ fifth biennial reports. In particular, the round table should take note of paragraph 182 which states that “projections from the BR5s indicate that no Party will achieve its targeted level of emissions in 2030 set out in its NDC.” This information, coming from the UNFCCC’s transparency arrangements, is particularly important in the context of discussing pre-2030 ambition- but whether it will actually feed into the discussion remains to be seen.

Second, the ‘Sharm el-Sheikh mitigation ambition and implementation work programme’ is on the agenda. As discussed in a previous blog, parties did not include transparency reports as a specific input into this work programme. The workpramme now centers around Global Dialogues that in 2023 centered around the topic of ‘just energy transition’ and investment-focused events. This is a far cry of what was on the table when the focus of the work programme was discussed in 2022.

Back then, transformative options were on the table (as expressed in an informal note). For example, developed countries proposed “enhancement of NDCs, including sectoral commitments” and the creation of “recommendations and road maps for delivering sectoral commitments.” Some developing countries feared that quantified targets could mean “imposing similar mitigation targets and goals for all Parties by or around mid-century without providing means of implementation for developing countries” and they argued for “the operationalization of the equitable distribution of the carbon budget, taking into account the historical responsibility of developed countries and climate justice.” And linked to this, were also proposals for new tracking, including tracking progress against sectoral benchmark indicators and a ‘global carbon budget tracker’. In the end, sectoral targets nor the carbon budget made it into the new mitigation work programme and no new tracking systems were developed. But these discussions remain at the heart of enhancing ambition.

Indeed, and thirdly, the first global stocktake, will likely see these issue flare up as well. The synthesis report of the technical dialogues under the global stocktake mentions, for example, the need for ‘systems transformations across all sectors’ but also that ‘equity can increase ambition.’ It does not, however, mention the ‘carbon budget’ as a way to operationalize this.

Will the political phase of the global stocktake make headway on these matters? This remains to be seen. The synthesis report lists a number of procedural follow-up activities, with the first one being the submission of biennial transparency reports. While the biennial transparency reports and new nationally determined contributions allow individual countries to reflect in these documents on the principle of equity and sectoral efforts, there are further avenues to discuss these multilaterally at COP28.

Source: Technical dialogue of the first global stocktake: Synthesis report by the co-facilitators on the technical dialogue. Available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/sb2023_09E.pdf.

Here a fourth, and particularly interesting, (provisional) agenda item for COP28 enters the picture: the LMDC group proposed a new agenda item titled: ‘Operationalization of the principles of equity and common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in accordance with Article 2, paragraph 2, of the Paris Agreement.’ Their submission does not reveal in detail what this group hopes to discuss under this agenda item. But the idea is probably to give a counterweight to the pre-2030 ambition round table and the mitigation work programme, that are more anchored in ambition than equity. Another point that might be raised is the carbon budget, and how to ensure equitable access to it.

Another agenda item of interest here is the ‘Second review of the adequacy of Article 4, paragraph 2(a–b), of the Convention.’ The first review took place in 1995 at the first COP and the review concluded that Article 4.2 is not sufficient, and this resulted in the launch of Kyoto Protocol negotiations.

The second review was initially on the agenda for COP4. But it proved impossible to reach consensus, and it has ever since. A key bone of contention is whether it is within the scope of the review to discuss if article 4.2 is insufficient in the sense that it does not apply to developing countries. For example, the United States proposed that the outcome of the review “Confirms that action by developed country Parties and other Parties included in Annex I alone will not be adequate to meet the objective of the Convention.” The G77 and China, instead wanted to focus on mitigation commitments of developed countries.

Later at COP7, the G77a and China proposed to reformulate the agenda item as “review of the adequacy of implementation of Article 4.2(a) and (b)” [emphasis added]. This would resolve different interpretations on what it is exactly that is to be reviewed, and whether this could result in more action being required from developing countries (see here for a detailed analysis).

The item is again on the agenda for COP28. Most likely it will be held in abeyance. But the balance of interests may start to change. Some developing countries are afraid that the Paris Agreement is increasingly being put to the fore while the Convention recedes to the background. The Convention is anchored more strongly in principles of equity and common but differentiated responsibilities. To bring the Convention back into the picture it may help to bring such agenda items, that have been held in abeyance for a long time, back alive.

Another process that is in transition is the Multilateral Assessment of biennial reports submitted by developed countries. From next year onwards developed countries will submit biennial transparency reports that undergo a process of Multilateral Consideration of Progress with common rules for developed and developing countries. One consequence may be a dilution in attention and rigour of the assessment of developed countries’ reports. Extra reason thus to take closer look of the last Multilateral Assessment for a group of developed countries scheduled to undergo this at COP28.

A number of important developed countries are set to undergo multilateral assessment at COP28. But soon the Multilateral Assessment will be replaced by a potentially more ‘soft’ Facilitative, Multilateral Consideration of Progress. Will COP28 end the multilateral assessment tradition with a bang? These are the ones to follow.

First, the Netherlands is up for review. One interesting point here is that in the Netherlands the highest court ruled that the country had to reduce emissions by at least 25% by 2020 below 1990 levels. Now the numbers are out and the government claims in its climate report to have reduced emissions by 25.5% (in the 2020 year of COVID lockdown). It will be interesting to see if anything related to this comes up in the verbal question and answer session at COP28.

In addition, Japan asked posed an interesting pre-session written question to the Netherlands: “According to the projection results provided on p156-157 of the NC8, the emission reduction target of 55% reduction of national total emissions from 1990 level by 2030 will not be reached under any of the “With Existing Measures” (WEM) scenario, the “With Additional Measures” (WAM) scenario, or the “With Scheduled Measures” (WSM) scenario. How are the results of the projections reported in the NC and the BR used in future policy making?”

Second, the EU is up for multilateral review. One interesting question posed by Canada points to a potential accounting ‘trick’ that makes the 55% reduction target of the EU look larger than it actually is. It will be interesting to see how the EU responds to this.

Finally, the US will undergo multilateral assessment. Again, some interesting questions set the tone for the session in Dubai. New Zealand asks in a pre-sessional written question “what measures has the US taken to reform, reduce and remove harmful fossil fuel and agricultural subsidies?” And further poses the questions “To what extent did the United States fossil fuel production increase or decrease over the period 2013-2020? What measures exist around approving new fossil fuel expansion?” Japan further asks “In the summary table of policies and measures, “direct ocean capture with durable storage” is mentioned as a CDR technology the program invests. What is technology or process considered as direct ocean capture?”

What this shows is that the Multilateral Assessment sessions may not be a merely procedural affair or an exchange of compliments. But whether the sessions will generate any tracking beyond the usual crowd of transparency experts remains to be seen.

COP28 will see push and pull on the transparency rules in various avenues. The red thread here is the transition from reporting and review under the Convention to the Paris Agreement.

Some contestations discussed above are about the new system under the Paris Agreement. Countries will discuss how support for reporting is organized, especially now that more rigorous and continuous reporting is required from developing countries.

But with the new becoming operational, a latent discussion is what to make of the old. Developed countries might seek to subtly ‘sunset’ every more processes under the Convention, and reporting might be one of them. Developing countries, however, do see continued relevance in reporting under the Convention. And there might even be an opening to reinstate synthesis reports of developing countries’ national communications.

Meanwhile, this COP will see several major developed countries undergo their last Multilateral Assessment and the principles and framing of Paris Agreement’s Facilitative, Multilateral Consideration of Progress are softer.

For now, transparency, with all its elaborate reporting and review, seems to remain rather detached from the venues where ambition is discussed. The big question is whether this dynamic will change in 2024 when both developed and developing countries are subject to the same transparency framework.

TRANSGOV representatives will be at COP28 to cover the latest transparency developments. Follow daily updates via the TRANSGOV twitter. For your reference, please find in the annexes below an overview of key transparency related events and publications for COP28.

Side events

| Day | Time | Location | Title |

| Friday, 01 Dec | 16:45—18:15 | SE Room 1 | Enhanced Transparency for Small Island Developing States |

| Friday, 01 Dec | 18:30—20:00 | SE Room 1 | Navigating Technical Expert Review under the ETF: Leveraging Existing MRV Insights for Success |

| Sunday, 03 Dec | 16:45—18:15 | SE Room 1 | Harnessing Transparency for Ambitious NDC Implementation in Central Asia |

| Monday, 04 Dec | 11:30—13:00 | SE Room 6 | Is the looking glass half full or half empty? Transparency for climate discussions and reporting |

| Monday, 04 Dec | 13:15—14:45 | SE Room 1 | Key tools supported by the UNFCCC secretariat to strengthen the ETF |

| Monday, 04 Dec | 15:10 – 16:10 | Capacity building Hub | Measuring capacity progress in climate transparency under the GST |

| Tuesday, 05 Dec | 13:15—14:45 | SE Room 2 | Enabling climate action through data, transparency and finance |

| Wednesday, 06 Dec | 11:30—13:00 | SE Room 6 | Satellite Observation contributing to GHG inventory, NDCs, and GST |

| Friday, 08 Dec | 11:30—13:00 | SE Room 5 | Benefits and burdens: Developing country experiences with participation in transparency arrangements |

| Friday, 08 Dec | 13:15—14:45 | SE Room 5 | Achievements of the CGE, upcoming activities and national insights on the preparation of BTRs |

| Saturday, 09 Dec | 18:30—20:00 | SE Room 2 | Nigeria and Sustainable Energy Africa (SEA), Monitoring & Evaluation of Just Transitions Event |

| Sunday, 10 Dec | 16:45—18:15 | SE Room 9 | Earth observations in support of mitigation actions towards the Paris climate goal and SGDs |

| Monday, 11 Dec | 11:30—13:00 | SE Room 7 | Climate Finance Transparency: a harmonized framework to mobilize public and private finance |

Also keep an eye out for the UNFCCC’s transparency calendar.

| Title | Organizations | Annotation |

| Benefits of Climate Transparency | PATPA, UNFCCC | This publication discusses the benefits of participation in climate transparency arrangements. It also includes various country case studies. |

| Trust and Transparency in Climate Action: Revealing Developed Countries’ Emission Trajectories | CEEW, Wageningen University & Research | This publication uses information as disclosed by developed countries in their biennial reports to shed a light on their mitigation performance. |

| A fit for purpose approach for reporting and review under UNFCCC’s Enhanced Transparency Framework | Tinus Pulles & Lisa Hanle | This publications highlights the logistical challenges related to the enhanced transparency framework, and offers suggestions for how to deal with them. |

| Opening the Black Box of Transparency: An Analytical Framework for Exploring Causal Pathways from Reporting and Review to State Behavior Change | Ellycia Harrould-Kolieb, Harro van Asselt, Romain Weikmans & Antto Vihma | This publication explores the relationship between participation in global transparency systems and state behavior change. |

Before COP27 we published this blogpost outlining 5 key processes related to transparency to follow. This blogpost reflects on the key outcomes.

As we reported in our pre-COP27 blog, under current transparency rules, there is no provision for technical review of information submitted on adaptation (and loss and damage). Key on the COP-27 transparency agenda was a request by developing countries to permit voluntary review of such information. Developed countries were not keen to have such information undergo review.

At COP27, Parties decided that countries may voluntarily submit information on adaptation (and loss and damage) for technical expert review.

One outstanding item was whether countries should be allowed to submit only one subsection of the adaptation section (crucially, one of the subsections is about loss and damage) for review. In Sharm-el Sheik, countries landed on the compromise text that if a country submits this section for review, all information in it will be reviewed, but certain sections can be identified for extra attention by the reviewers.

The hope is that including adaptation information in the review process will help to improve adaptation reporting capacities. As noted by an attendee at a COP27 #Together4transparency event, the focus of reporting capacity is often on emissions and mitigation. Similarly, earlier TRANSGOV work (link and link) has shown how capacity building programmes tend to focus less on adaptation. Whether this new provision to allow for voluntary review of adaptation information will help to improve adaptation reporting capacities remains to be seen.

Read the adopted decision text on this matter.

As we reported in our pre-COP27 blog, reporting on use of market mechanisms (Article 6) was a key item on the agenda. Article 6.2 allows countries to bilaterally or multilaterally trade emission reduction credits and then report on these trades, with this information undergoing review before being made public. However, countries can mark certain information as ‘confidential’. At COP27, Parties were to decide the scope of this confidentiality provision.

Confidentiality provisions under article 6.2 were up for debate till the very last minutes of COP27.

The decision text on article 6.2 allows countries to identify certain information as confidential, thus not publicly available. However, countries should then justify why the information is confidential. Technical reviewers can still review the information and shall publish inconsistencies found, but in a manner that does not compromise confidentiality of the information.

The SBSTA will continue to further discuss modalities of review of confidential information at the next session. Countries can submit their views on this matter before the next June intersessional.

The fear is that evoking confidentiality may hide emission reduction credits of questionable integrity.

Another key issue that emerged, under article 6.4, was loopholes that would allow the selling of emission reductions twice (or even more). Despite detailed rules for GHG inventories, such trades could give a false sense of emission reduction achievements.

COP26 decided that host countries, where projects generating credits are based, should make ‘corresponding adjustments’ when selling credits to other countries. However, this only applies to ‘authorized’ credits. At COP27, a key question was what to do with unauthorized credits. COP27 ultimately termed these credits ‘mitigation contributions’, based on the philosophy that buying these credits should be seen as a form of (international) financing of emission reductions that will count towards the NDC target of the host country, rather than offsetting the buyer’s own emission reductions. However, the system is not watertight and buyers may in practice still count the credits towards their own climate goals.

Tricky issues related to emissions avoided and emission removals will be discussed at future sessions.

As we reported in our pre-COP27 blog, Parties were to consider ‘compilation and synthesis’ reports prepared by the UNFCCC secretariat that synthesized the performance of developed (annex I) countries, as reflected in their transparency reports. This is valuable source of information about such performance.

As expected, however, the COP decided to defer consideration of the Annex I BR synthesis report to the next session. The reason? Russia reports emissions from Crimea. Ukraine and allies thus oppose giving such a synthesis report any formal consideration. This is unfortunate because these reports contained valuable politically salient information on how developed countries performed on their 2020 mitigation and climate finance targets, as we explain in detail in our pre-COP27 blog.

Looking forward, under the Enhanced Transparency Framework (ETF), the UNFCCC secretariat is mandated to write a synthesis report of Biennial Transparency Reports (BTRs) (18/CMA.1 paragraph 6(a)). This may lead to further negotiations— either before or in response to the first synthesis report. One question is whether the report should be disaggregated by developed and developing countries.

As we reported in our pre-COP27 blog, perhaps one of the most prominent and contentious expectations for COP27 was to address financing for loss and damage.

A key outcome of COP27 is the establishment of a fund to respond to loss and damage.

A close reading of the decision text shows that parties established new funding arrangements (plural) and that one component of this is a new loss and damage fund.

It remains to be determined what the funding arrangements landscape will look like, and what role the newly established fund will play vis-à-vis other funding arrangements. One question we are interested in is how parametric insurance enabled by novel forms of satellite-enabled data relates to this, and whether such insurance-based instruments may crowd out public finance via the fund.

It is worth noting that the decision text does not mention that funding should be public and grant-based, despite calls for this by developing countries.

Although the decision text does not mention insurance either, it does mention the ‘Global Shield’ (an approach piloted by Germany and a host of private actors outside the auspices of the UNFCCC to address loss and damage through insurance schemes), as well as the need for ‘speed’ in reacting to instances of loss and damage. These elements provide avenues for the promotion of insurance—enabled through new forms of radical satellite-enabled transparency— as key to loss and damage financing. TRANSGOV will continue to follow this topic closely.

As we reported in our pre-COP27 blog, the last year has seen the launch of the ‘work programme to urgently scale up mitigation ambition and implementation in this critical decade’. Transparency is presented as the backbone of ambitious climate action under the Paris Agreement and a key source of information about country performance. Will the mitigation work programme draw on transparency reports? Or will the two remain politically detached?

The decision text on the mitigation work programme does not mention Biennial Transparency Reports as a source of input. Instead, the only clear input to the work programme is to be targeted submissions by parties and non-party stakeholders. The transparency system thus remains detached from this important new agenda item that is explicitly designed to address the raising of collective ambition.

This seems to be a trend rather than an anomaly. For example, the Glasgow Climate Pact does not make any reference to findings from country transparency (BR or BUR) reports. Instead, information emphasized here is the forward-looking findings from the NDC synthesis report. The fact that these findings are not in line with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5-degree target is cited as the main reason for the need to double down on mitigation efforts. It is surprising however that no reference is made to actual findings from Parties’ transparency reports that cover implementation of targets.

It seems that the transparency arrangements and ambition-related negotiations remain politically detached. TRANSGOV will continue to follow this topic closely.

While participating in COP27, two additional transparency-related matters caught our attention. First, the obscure but consequential agenda item on ‘bunker fuels’- that is, aviation and shipping; and second, the buzz around getting ready for the ETF.

Hidden under ‘methodological items under the convention’, we find the agenda item on bunker fuels. Bunker fuels are defined as all fuels sold for international aviation and shipping.

The UNFCCC has a clear explainer on this:

“The IPCC Guidelines for the preparation of greenhouse gas (GHG) inventories, the UNFCCC reporting guidelines on annual inventories for Parties included in Annex I to the Convention (Decision 24/CP.19), and the Modalities, procedures and guidelines for the transparency framework for action and support referred to in Article 13 of the Paris Agreement (Decision 18/CMA.1) outline that emissions from international aviation and maritime transport (also known as international bunker fuel emissions) should be calculated as part of the national GHG inventories of Parties, but should be excluded from national totals and reported separately.

These emissions are not subject to the limitation and reduction commitments of Annex I Parties under the Convention and the Kyoto Protocol due to the fact that they are not accounted in national totals.”

Source: https://unfccc.int/topics/mitigation/workstreams/emissions-from-international-transport-bunker-fuels

In simple terms, this means that emissions from international shipping and aviation do not count towards any country’s emissions.

This is reason for concern because these emissions are on the rise:

Rather than counting these emissions in the inventories, the UNFCCC is ‘in dialogue’ with ICAO and IMO to keep tabs on how these organizations aim to reduce emissions and how they are counted. At COP27, these organizations gave a presentation and they provided answers to some but not all questions.

The Sharm el-Sheik Implementation Plan contains a dedicated section on transparency. This short section recalls the deadline for submission of the first BTR and urges parties to make necessary preparations to meet this deadline. It further recognizes the need for increased support to developing countries for implementing the ETF.

During COP27, the UNFCCC secretariat organized 25 events under the banner #Together4Transparency. The event series is to celebrate past achievements and “pave the way for the full implementation of the Enhanced Transparency Framework (ETF) of the Paris Agreement”.

The event series included various organizations that provide capacity building support. As mentioned by one speaker, “there is support out there”. It seems that donor countries are relatively willing to spend resources on ensuring that developing countries meet the Paris Agreement’s transparency obligations.

One session was titled “Benefits and tools for implementing the Enhanced Transparency Framework”.

The UNFCCC secretariat presented a list of benefits that may result from participating in the UNFCCC transparency arrangements.

TRANSGOV will do further empirical research to analyze what the consequences of participation in transparency arrangements are in practice, particularly in relation to climate action. We will do this also through in-depth country case studies.

Transparency did not make headlines at this COP-27. However, transparency related fights flared up in various other negotiations, including climate finance, mitigation ambition and market mechanisms. This said, the overall picture that emerges is that of an isolated transparency framework. There are few institutional linkages between the transparency framework and other politically contentious negotiation processes aimed at ramping up ambition, like the mitigation work programme or the discussions on the new collective quantified goal on climate finance. Even as this is so, efforts to get as many developing countries up to speed with UNFCCC and ETF reporting requirements continue unabated.

COP27 is around the corner. What to expect for transparency negotiations? At first glance, it may seem like intensive transparency negotiations are now a thing of the past. The rules for the Enhanced Transparency Framework of the Paris Agreement are described by the Modalities, procedures and guidelines from Katowice and the reporting guidance from Glasgow. What is left for transparency at COP27? This blogpost highlights that transparency’s tentacles penetrate various domains of the UNFCCC. We highlight five processes to follow to understand how transparency’s role in climate governance evolves.

Glasgow marked the end of six years of tedious negotiations to hammer out the detailed transparency rules under the Paris Agreement. Or, so it seemed. In Bonn last June, negotiations re-opened on the question of whether information related to adaptation and loss and damage could undergo technical review on a voluntary basis.

Under current rules, there is no technical review of information on adaptation and loss and damage as reported by countries. Yet, adaptation and loss and damage are important topics for developing countries.

Developing countries argue they should have the opportunity to ask for voluntary review of this information. The quality of reporting on adaptation and loss and damage is far behind mitigation. Undergoing technical review may improve reporting capacity.

Developed countries are less keen to have adaptation and loss and damage undergo review. They fear the international community will spread its resources thin if too many types of information have to be reviewed. Thus, developed countries defend, the focus should be on emissions and mitigation.

In Bonn, it became clear that the idea of a voluntary review option was politically palatable. However, the devil is in the detail- this one a detail with implications for review of loss and damage information.

Under the Paris Agreement adaptation and loss and damage are treated as two separate items, each with its own article. However, under the transparency rules, loss and damage is a subsection under the category ‘adaptation and climate impacts’.

The discussion in Bonn centered around whether countries should be allowed to only submit one subsection (i.e. loss and damage) for review, if they wish so. Developed countries were against. This matter remains bracketed in the text going into COP27 (See draft text para 3: “decides that the Party undergoing the review referred to in paragraph 1 above may elect all information or specific topics within the information reported”).

Another discussion in Bonn centered around whether the review team should include loss and damage experts. And whether the training programme for reviewers should have a separate module on loss and damage. But these suggestions did not make it to the draft text coming out of SB56 in Bonn.

“AOSIS members wanted an option for loss and damage experts to review the voluntary information that we report. This proved too much to ask.”

– AOSIS closing statement submission at SB56 in Bonn

At COP27, negotiators will finalize the decision text on this matter. This discussion illustrates the political nature of transparency negotiations. Moreover, it shows how contentious issues (e.g, how much attention for loss and damage) get hammered out in operational detail in the transparency negotiations.

Under the umbrella of Article 6 (market mechanism) negotiations, Parties will discuss the details of reporting on the use of market mechanisms.

As highlighted by a carbonmarketwatch.org article the question for COP27 is: “will countries agree to full transparency on carbon credit trades under Article 6.2?”

Article 6.2 allows for countries to bilaterally or multilaterally trade emission reduction credits. Countries have to report on these trades and this information then undergoes review which is in turn made public.

However, the current rules have a provision where countries can mark certain information ‘confidential’. At COP27 Parties will debate this confidentiality provision. Carbon brief did an analysis of country positions for COP27. Like Minded Developing Countries want all information to be treated as confidential by default. The EU, Small Island Developing States, and Least Developed Countries oppose such blanket confidentiality.

COP27 will also feature agenda items on pre-Paris transparency arrangements. Two sub-agenda items are of particular interest.

First, Parties will consider ‘compilation and synthesis’ reports that capture the performance of developed (annex I) countries (agenda item SBI 3b). Under the convention, developed countries have to submit Biennial Reports on progress towards mitigation pledges and climate finance. The UNFCCC secretariat then drafts a ‘compilation and synthesis’ report that shows overall progress of annex one countries on mitigation and climate finance.

Upon publication of these reports, Parties are to ‘consider’ its content. This is a sticky point. Parties did not manage to agree on their consideration of the ‘compilation and synthesis’ reports from 2016, 2018, and the recently updated report from 2020.

An example, of information in this report includes aggregated figures of time-series of annex-1 Party emissions and climate finance.

It remains to be seen if Parties can conclude their consideration of these reports at COP27.

The other outstanding item also involved ‘consideration’ of reports (agenda item SBI 4a). This time reports submitted by developing countries (non-annex 1). Back in 2006, some Parties argued that under Article 10.2 of the Convention the SBI is to consider National Communications by non-Annex 1 countries (developing countries). This agenda item has since been held in abeyance. At COP27 Parties are invited to provide guidance on how these reports may be considered.

These ‘considerations’ are moments where reporting meets the political process. Reporting is one thing, but to act on the findings of the reports- or to agree on the content in the reports- is another.

Perhaps one of the most prominent and contentious expectations for COP27 is to move forward on finance for loss and damage. The G77/China submitted a new agenda item on this matter for COP27 titled “Matters relating to funding arrangements for addressing loss and damage”.

While finance for loss and damage is no longer taboo, views on how to operationalize it diverge. One approach piloted by Germany and a host of private actors is to address loss and damage through insurance schemes.

Transparency is a crucial factor here. First, novel technologies such as satellite-based monitoring make possible new parametric insurance products for extreme weather events such as drought. Second, donor countries will want to report on the finance provided to these insurance schemes as climate finance. But views diverge as to how amounts should be calculated. Moreover, much uncertainty persist around whether and how insurance schemes will align with principles of climate justice such as polluter-pays and common but differentiated responsibilities enshrined under the Convention.

Ambition is a word that sparked fierce debate at the previous climate talks in Bonn. The latest synthesis report shows that countries are off track to keep temperatures below the agreed 2 degree goal, let alone 1.5. (Similar conclusions in the second periodic review).

In Glasgow, the ‘work programme to urgently scale up mitigation ambition and implementation in this critical decade’ was established to ramp up ambition. In Bonn, discussions on operationalizing this programme were contentious and did not yield any outcome documents.

If the mitigation work programme is to ramp up ambition, then what does it draw on to discuss who should do more and when?

Transparency is often assumed to be the backbone of ambitious climate action and the key source of information. Will the mitigation work programme at any point draw on transparency reports? Or do the two remain politically detached?

Nothing is set in stone yet. The AOSIS submission to the work programme suggest that Biennial Transparency Reports will be an input for the work programme. By contrast, Australia and Norway do not list Biennial Transparency Reports as inputs. Rather, they prefer NDC and long-term net-zero pledges as inputs. This may indicate their reluctance to have scrutiny about actual past implementations.

Transparency may not make the headlines this year. However, its tentacles penetrate various domains of high-stake negotiations, including loss and damage and enhanced ambition. Moreover, routine negotiations to consider transparency reports have proved difficult. At the same time there are a series of events about ‘getting ready for the ETF’ under the #together4transparency initiative. What does this mean for the prospects of the Enhanced Transparency Framework? These and other questions remain open-ended and will be on our mind during COP27.

TRANSGOV representatives will be at COP27 to cover the latest transparency developments. Follow daily updates via the TRANSGOV twitter.

Capacity building for climate transparency is generally understood as a neutral means to ensure all countries have the capacity to report information to the UNFCCC. However, an earlier TRANSGOV article problematized this proposition and highlighted that capacity building may in practice steer the type of transparency generated by countries and influence politically contested discussions over who is to be transparent about what to whom. In particular, the article interrogated whether and how capacity building initiatives steer or preempt options for developing countries trying to navigate between adhering to global transparency provisions (which emphasize transparency of emissions and mitigation action) versus furthering domestic aims (which may relate more to generating information on adaptation, loss and damage, and finance).

The article called for empirical analysis of capacity building in practice. This blogpost takes a next step in this line of research and presents a database of capacity building for climate transparency projects as a first step in taking this research agenda forward and as a resource for others to use as well.